In my last article entitled “Improving leadership potential” I wrote about the need to have clarity about expectation and current state. The diagnostic phase…

Having undertaken rigorous diagnosis, attention now moves to the process of ‘shifting the needle’… One of my best friends and a genuine mentor for many years, Glenn Dobson, owns the KONA Group. One of its core offerings is in salesforce capability development. Over the years I have heard Glenn share with prospective clients, repeatedly, “As the owner of a training business, can I tell you that most training is a complete and utter waste of time…” and he’s right. Especially in the leadership development space. At the risk of being contentious I put it to you that too many leadership development businesses aren’t. They’re event management businesses. Sell a place in a workshop, provide some interesting content accompanied by amazing models delivered in Prezi, some high-tempo music at the end of the morning and afternoon teas, then send an invoice. Next please!

Now don’t get me wrong, workshops do have a role to play in improving leadership potential. But the ratio has to be considered. The latest thinking along these lines – which we also subscribe to – is the 70:20:10 model.

As the representation above shows the essence of this approach is that learning & development achieves best outcomes when it is 70%—informal, on the job, experience based, stretch projects and practice 20%—coaching, mentoring, developing through others and 10%—formal learning interventions and structured courses… aka workshops. The 70-20-10 rule emerged from 30 years of the Centre for Creative Leadership’s (CCL) “Lessons of Experience” research, which explores how executives learn, grow and change over the course of their careers. It values the on-the-job informal learning that is often more effective, less expensive and more relevant. But informal doesn’t have to mean random – paired with clear direction, relevant situations, supportive feedback and a guiding framework, informal learning can be instantly applicable and transformative.

Challenging to apply and now questioned by some, the 70-20-10 concept and proportions should be considered a guide rather than a rule. It is an idea that seeks to foster learning from experience, lifting internal collaboration and dialogue in the way we develop our people.

“The underlying assumption is that leadership is learned,” says CCL’s Meena Surie Wilson. “We believe that today, even more than before, a manager’s ability and willingness to learn from experience is the foundation for leading with impact.”

The 70-20-10 rule seems simple, but you need to take it a step further.

All experiences are not created equal. Which experiences contribute the most to learning and growth? And what specific leadership lessons can be learned from each experience? For the last 10 years most leadership development that I have facilitated has had a strong application component. Typically this involves the participant identifying a business improvement need – in any area: it could be employee engagement, customer satisfaction, financial performance or process improvement or any other aspect which would benefit the business and derive a demonstrable return-on-investment. This creates a real-world scenario whereby the participant can be applying their new skills, process, methodology etc., receive coaching/guidance/mentoring on the job and deliver improvements to the business. This approach has proven very powerful.

Over the nearly two decades that I've been working with people to help them develop these skills there has been that perennial question of nurture vs. nature. In other words is leadership natural, innate and pre-loaded when certain individuals are born or can it be taught? Personally, I find the question annoying... because the answer is "yes". Some folks do seem to have a natural inclination to be able to garner willing followership and equally as many have learned to do what is necessary. And both can be equally as effective as the other.

But it's also true that some people, who hold senior roles in organisations (by default therefore, 'leaders') struggle to have people follow them, let alone catalyse discretionary effort. Why is that? From where I stand it seems to me that they just don't have the heart for it.

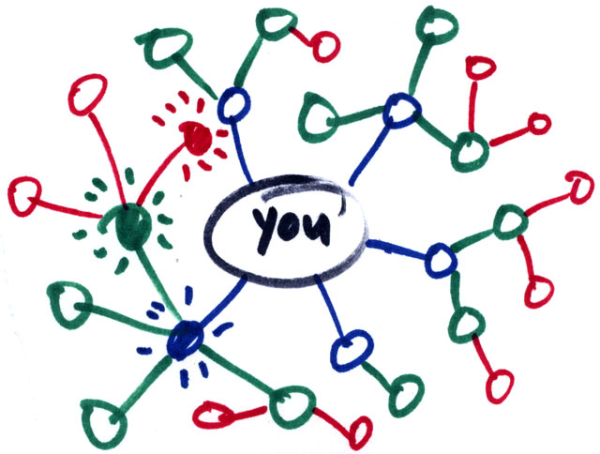

You see, leadership is human. You can't lead an inventory. You can't lead a spreadsheet. You can't lead a brand. They're all inanimate objects and they won't follow you anywhere. You can (and should) mange those things. But you can't lead them. To lead is to win the hearts and minds of those that would follow - to garner trust in them. And that means that leadership is all about building and maintaining relationships - with human beings. I'm not sure I've ever seen a relationship last where either party didn't 'have their heart in it'.

Over the many years that my colleagues and I have been coaching our clients on the subject of leadership what we have routinely found is that central to any success or failure of leadership is the character of the individual doing the leading. When I have worked with very senior executives in positions of significant power - and where those individuals have received less than gratifying 360-degree feedback on their leadership effectiveness, has that been because they don't know or possess the skills to lead? Of course not. For the most part, the negative feedback is borne not from what they do but from how they do what they do. It's about the behaviour which accompanies the action - the style, if you will - their character... or 'heart'.

So, from experience, I would advise anyone wanting to improve leadership potential to focus equally as much on the behaviour/nature/character of each individual as you do the skills/processes/methodologies of leadership.